On 30 March 1976, after the Israeli government published a plan to expropriate Palestinian lands for state use, along with an order to impose a curfew on several Palestinian villages, the Palestinian community in Israel called for a general strike and protests throughout the country. Israeli police and military killed six protestors, injured hundreds, and arrested hundreds more. Palestinians now commemorate March 30th as Land Day.

Many claim that the protests in 1976 reaffirmed the Palestinians in Israel as part of the Palestinian nation. This claim is unfounded for two reasons. First, the Palestinians in Israel have publicly expressed their Palestinian identity while subversively resisting Israeli rule since 1948. In the 1950s they formed al-Ard, a small Palestinian pan-Arab political group, which the Israeli authorities banned shortly after it was founded. They also expressed their aspirations as Palestinians through the vehicle of the Israeli Communist Party. Second, various historical events indicate that the rest of the Palestinian people included them in the umbrella of the “Palestinian nation” almost a decade before Land Day – since 1967. The Land Day protests were the largest, rather than the first, Palestinian collective mobilization in Israel. Today, Land Day offers a fascinating case study in representation, mobilization, and the contours of the Palestinian nation.

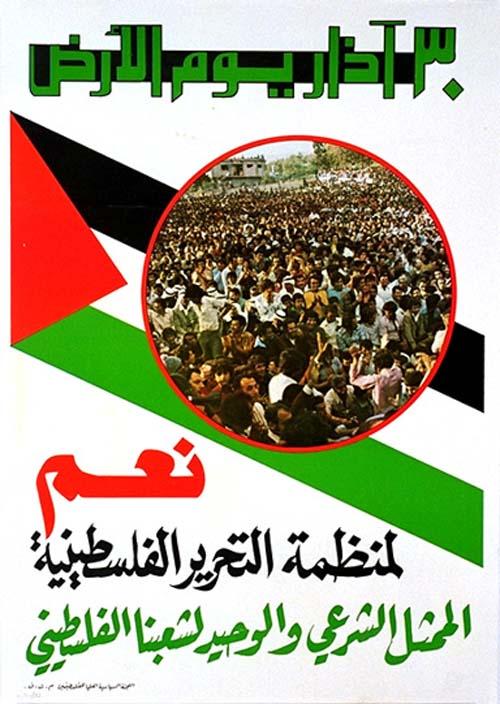

Palestinian nationhood, like any other nationhood, is flexible. Nations are imagined collectives, but they do maintain rules for eligibility. For Palestinians, a fracturing experience like exile, coupled with colonialism and occupation, further complicates the nation and problematizes the issue of national representation. Even though the international community officially recognized the Palestinian Liberation Organization as the “sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people” in 1974, representation remains thorny.

These complications become particularly salient when it comes to Palestinians who are citizens of Israel. Their legal status rendered them geographically isolated in a time of limited communication, and therefore they had their own structures for representation based on their unique status as (unequal) Israeli citizens.

These Palestinians were the parents, children, and siblings of exiles. The Israeli state was keenly aware of their presence and placed them under martial law immediately in 1948. Largely owing to their resistance to military rule and their persistent self-identification as Palestinian Arabs, the indigenous minority created paranoia among Israeli policymakers. In a failed attempt to gain their allegiance, Israel lifted martial law in 1966. Israel had been confiscating the Palestinian citizens’ lands for the previous three decades, and still does today. But in the 1970s, without the restrictions of martial law, Israel’s Palestinian citizens had greater capacity to mobilize. Palestinian citizens of Israel also had a complicated relationship with the Palestinian communities outside of the Israeli borders, characterized by generations of physical separation and difficult communications.

In the early years, this particular Palestinian demographic’s geographic isolation and their status as citizens of Israel sometimes rendered them a lost cause in the eyes of other Palestinians. At times, Palestinians on the outside considered Palestinian citizens of Israel to be an “other,” a lost sibling co-opted by Israel. As Edward Said wrote in his memoir Out of Place:

…as recently as the early 1970s, I can recall, Israeli Palestinians were considered a special breed—someone you might easily be suspicious of if you were a member of the exile or a refugee Palestinian population residing outside Israel. We always felt that Israel’s stamp on these people (their passports, their knowledge of Hebrew, their comparative lack of self-consciousness about living with Israeli Jews, their references to Israel as a real country, rather than ‘the Zionist entity’) had changed them. (51)

There had always been a clandestine flow of literature and communication between Palestinians on the inside and on the outside.[1] For exiled Palestinian communities, however, this did not translate into a broader awareness of the conditions of the Palestinians on the inside – of their self-identification, or of their resistance to Israeli rule. Until 1967, that is, when things started to change.

In 1967, after Israel occupied the remainder of historic Palestine, as well as the Golan Heights and the Egyptian Sinai, the borders briefly opened. Palestinian refugees traveled back en masse to visit their confiscated homes and their estranged relatives living within the 1948 Armistice Line. This moment was immortalized by Ghassan Kanafani in Returning to Haifa and by Emile Habibi in The Six Days Sextet. The moment was short-lived, and the borders were sealed immediately thereafter, but the language about the Palestinians on the inside began to change irreversibly – even in the PLO’s official communications.

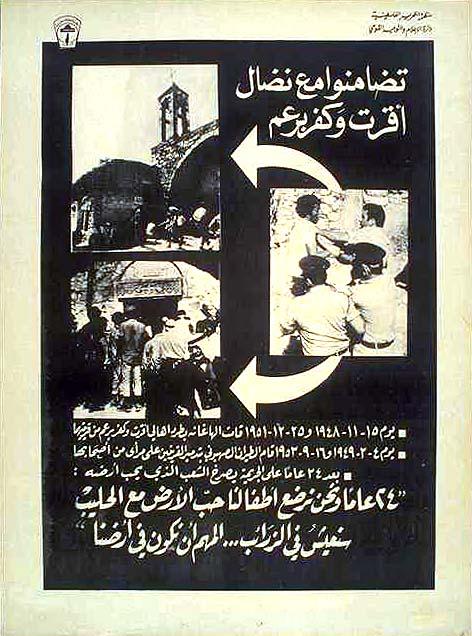

For example, this 1972 poster publicizes the struggles of the Palestinians who remained in their villages and whom Israel internally displaced in the early 1950s:

The PLO, which was largely composed of refugees, took a keen interest in mobilizing the Palestinian community in Israel. Part of this, perhaps, was sentimental. Yet a larger part was strategy. The PLO wanted to take military resistance across the border and into Israel. But it had little success. In the late 1960s the Palestinian community in Israel had only recently escaped martial law, under which the Israeli state policed Palestinian activities and movements very closely. Even after it lifted martial law, Israeli society continued to be suspicious of the indigenous Palestinian minority, particularly in the context of the growing popularity of the PLO among Palestinians elsewhere.

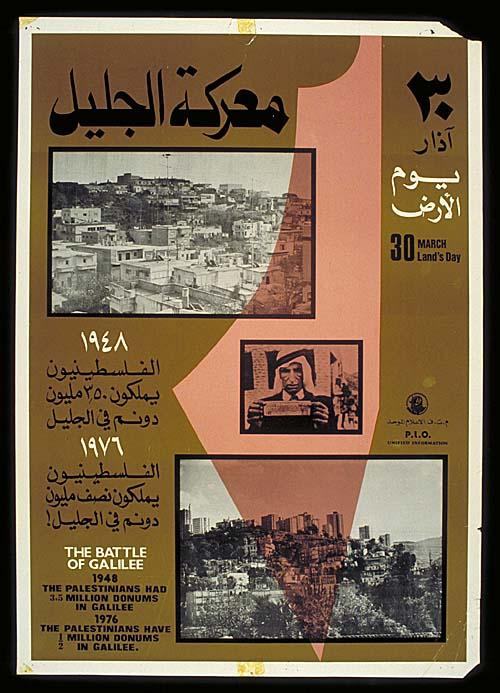

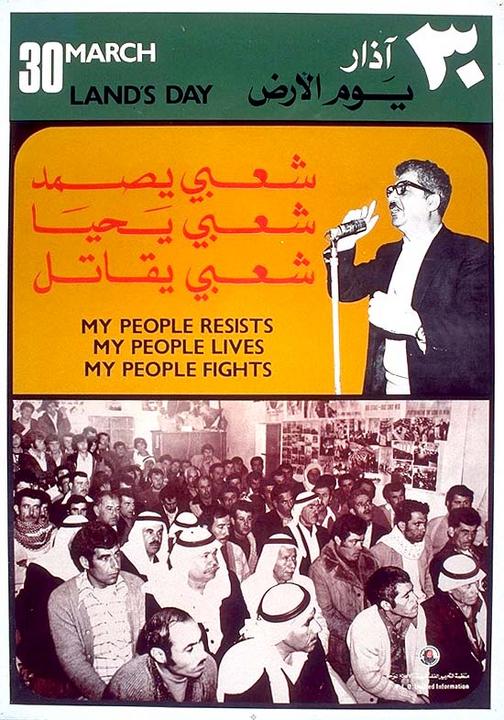

Later, in March 1976, what the PLO probably saw as an opportunity to mobilize the revolting Palestinians in Israel was lost as it became embroiled in the Lebanese Civil War. Nevertheless, solidarity protests that took place on 30 March 1976 in the West Bank, Gaza, and in several refugee camps around the Arab world further indicate that by 1976 Palestinians already felt an affinity towards their counterparts inside Israel. The PLO’s Land Day commemoration posters capture the spirit of the times and offer perspective on the PLO’s position vis-à-vis the Palestinians in Israel.

At times, these posters’ contents reflect a common language between public figures from the Palestinian community in Israel and the PLO.

For example, this poster identifies Israeli land confiscation in 1976 as a continuation of land confiscation in 1948. This continuity highlights the similarities between the injustices done to the Palestinians residing on either side of the 1948 Armistice Line, and minimizes the differences:

In an address delivered in New York City after Land Day, and printed in the Autumn 1976 issue of Journal of Palestine Studies, Palestinian poet and then-mayor of Nazareth Tawfiq Zayyad likewise identified land confiscation in the 1970s as an extension of the 1948 policy:

The number of Arab villages in the area on which Israel was established was 585. Since the establishment of the state, this number has gone down to 107 villages. (94)

Still, the PLO did take liberties with the language it used to speak about the Land Day events. In the late 1960s, after an internal struggle, armed resistance became the PLO’s central strategy. In turn, the PLO labeled Land Day a “battle.” Ma’rakat al-jaleel – or the Battle of the Galilee, as the poster calls it – invokes the PLO’s own resistance tactics (think ma’rakat al-karama). Yet Israel’s Palestinian citizens were not preparing for military combat against the Israeli state. They marched as civilians, and the state retaliated against them with great violence.

Within the Palestinian community in Israel there was no consensus on the relationship with the PLO. Israeli authorities feared that the Palestinians would gravitate towards the PLO in light of their ongoing resistance to discriminatory and oppressive Israeli policies, and their self-perception as Palestinians. Yet Palestinian citizens of Israel had a multiplicity of views, made clear by their leaders’ public discourse. Still, the PLO informally presented itself as representative of the Palestinian community in Israel. This Land Day poster, for example, features a crowd of Palestinians – most likely from within Israel – and reads, “Yes to the Palestinian Liberation Organization, the legitimate and sole representative of our Palestinian people.”

Even though by the mid-1970s the majority of its membership hailed from the exiles in the refugee camps, the PLO considered its jurisdiction to extend over the entirety of those who call themselves Palestinian. This is visible in another poster, which declares, “My people resist, my people live, my people fight.” The photos of their gatherings indicate “my people” are the Palestinian citizens of Israel:

Once again, this informs the conversation about the PLO’s position towards both the Palestinian citizens of Israel themselves and their struggle: that they are part of the broader Palestinian struggle for rights on multiple levels and in multiple ways.

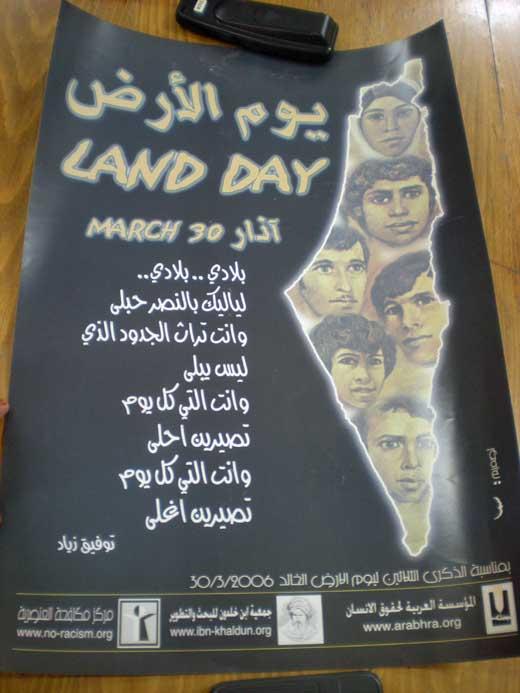

While Land Day continues to honor the events of 30 March 1976 in the Galilee, it has since become a broader commemoration of the loss of Palestinian land. The later PLO-produced Land Day posters focus less on Palestinian citizens of Israel and more on the land itself, although they still often feature the six murdered protesters:

Land Day was neither the first nor the last organized act of resistance by Israel’s Palestinian citizens. Nor did it represent a newfound Palestinian national consciousness for the Palestinian citizens of Israel, who had long self-identified as Palestinian. Indeed, the barriers between Palestinians in Israel and those in exile started coming down in the brief moment that the borders of Israel opened to the refugees in 1967. Instead, Land Day represents a more complex dialectic between the Palestinian citizens of Israel and the PLO, with the latter’s desire for a presence inside of Israel and the former’s geographic isolation.

A full collection of Land Day posters can be found at the Palestine Poster Project Archive.

[1] The inside/outside dichotomy is a shorthand way of speaking about Palestinian citizens of Israel (inside the 1948 Armistice Line; Falastiniyyet al-daakhil) and Palestinians in the Diaspora (particularly the refugees who reside outside of historic Palestine; Falastiniyyet al-shataat).